The following excerpt comes from Martin Heidegger’s Phenomenological Interpretation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, based on a lecture course he taught at the University of Marburg in the winter semester of 1927-28. At the outset of the course, he delivered these remarks on the philosophical character of doing the history of philosophy.

First, we must know what is means to understand a philosophy that has been handed down to us; secondly, we need a provisional knowledge of the ways and means of achieving such an understanding.

In the last years of his life, in the course of a conversation, Kant once said: “I came with my writings a hundred years too early. A hundred years from now they will understand me better and will study and accept my books anew.” Are we hearing here the vanity of self-importance, or even the annoyance and resignation of not being recognized? Nothing of the sort. Both are foreign to Kant’s character. What gets articulated in this quotation is Kant’s vivid understanding of the manner in which philosophy is realized and gets worked out.

Philosophy belongs to the most original of human endeavors. In this regard Kant remarks: “But these human endeavors turn in a constant circle, arriving again at a point where they have already been. Thereupon materials now lying in the dust can perhaps be processed into a magnificent structure.” It is precisely these original human endeavors that have their constancy in never losing their questionable character and in thus returning to the same point and finding there their sole source of energy. The constancy of these endeavors does not consist in the continued regularity of advancing, in the sense of a so-called progress. Progress exists only in the realm of what is ultimately unimportant for human existence. Philosophy does not evolve in the sense of progress. Rather, philosophy is an attempt at developing and clarifying the same few problems; philosophy is the independent, free, and thoroughgoing struggle of human existence with the darkness that can break out at any time in that existence. And every clarification opens new abysses. Thus the stagnation and decline of philosophy do not mean not-going-forward-anymore; rather they point to having forgotten the center. Therefore every philosophical renewal is an awakening in returning to the same point.

Let us learn from Kant himself about the issue of how to understand philosophy properly:

No one attempts to establish a science unless he has an idea upon which to base it. But in the working out of the science, the schema, nay even the definition which he first give to the science, is very seldom adequate to his idea. For this idea lies within reason, like a germ in which the parts are hidden, undeveloped, and barely recognizable, even under microscopic observation. Consequently, since sciences are devised from the point of view of a certain universal interest, we must not explain and determine them according to the description which their founder gives of them, but in conformity with the idea which, out of the natural unity of the parts that we have assembled, we find to be grounding in reason itself. For we shall then find that its founder, and often even his most recent successors, are groping around for an idea which they have never succeeded in making clear to themselves; and consequently they have not been able to determine the proper content, articulation (systematic unity), and limits of the science.

Applied to Kant himself, this means that we are not supposed to hold onto the merely literal description which he, as the founder of transcendental philosophy, gives of this philosophy. Rather, we must understand this idea–i.e., the determinant parts in their entirety–from out of that which grounds the idea. We must return to the factual ground, behind what is rendered visible by the first description. Thus, in grasping a philosophy which is handed down to us, we must comport ourselves in a manner which Kant emphasizes with regard to Plato’s doctrine of ideas:

I need only remark that it is by no means unusual, upon comparing the thoughts which an author has expressed with regard to his subject–whether in ordinary conversation or in writing–to find that we understand him better than he understood himself, in that he has not sufficiently determined his concept and therefore has sometimes spoken, or even thought, in opposition to his own intention.

According to this, then, to understand Kant properly means to understand him better than he understood himself. This presupposes that in our interpretation we do not fall victim to the blunders for which Kant once blamed the historians of philosophy, when he said: “Some historians of philosophy cannot see beyond the etymologies of what ancient philosophers have said to what they wanted to say.” Accordingly, to understand properly means to concentrate on what Kant wanted to say–that is, not to stop at his descriptions, but to go back to the foundations of what he meant.

…

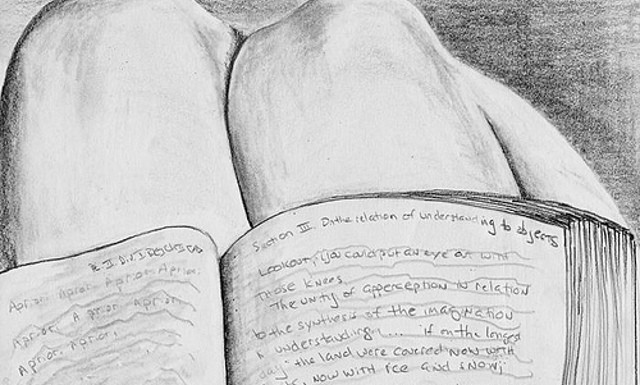

In order to see clearly what Kant wanted to say, we must familiarize ourselves with the text, by knowing the structure of the whole work, the inner connection among the individual parts, the interpenetration of the series of proofs–knowing the concepts and principles. It seems easy simply to state what is there in the text. However, even if we thoroughly appropriate the concepts, the question, and the conditions–by clarifying them or by determining their origin from out of the tradition and their transformation in Kant–even then we do not yet grasp what is in the text. In order to go that far, we must be able to see what Kant saw, as he determined the problems, came up with a solution, and put into the form of the work that we now have before us as the Critique of Pure Reason. It is of no use to repeat Kantian concepts and statements or to reformulate them. We must get so far that we speak these concepts and statements with Kant, from within and out of the same perspective.

Thus, to come to know what Kant means demands that we bring to life an understanding of philosophical problems in general. However, the introduction of philosophical problems will not precede the interpretation. Rather, through the acts of interpretation we shall grow into the factual understanding of the philosophical problematic. It will then become clear that and how Kant took an essential step in the direction of a fundamental elucidation of the concept and method of philosophy.

…

When the inherent structure of the Critique of Pure Reason calls for it, we shall on occasion deal with Kant himself, with his philosophical and scientific development, with his relation to the tradition and to what came after him. Thus these historical considerations shall also support and complete the interpretation. To this end we must also consider other writings of Kant. However, the first and foremost goal is to understand philosophically the unified whole of the Critique of Pure Reason.

The designation of this interpretation as “phenomenological” is meant initially to indicate only that coming to grips with Kant takes place directly within the context of the current and living philosophical problematic.

Martin Heidegger, “Preliminary Consideration”

Phenomenological Interpretation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, translated by Parvis Emad and Kenneth May